It’s that time of year again, where academics realise they no longer know how to relax, and yet have promised themselves most sincerely to not do any work. Updating my blog isn’t work though, right?

The subterranean traps are one of the most novel and exciting parts of my work, and as such I have received a lot of contact through this blog from people wanting to give them a try. As such, I really should tell what I’ve found so far, and my next steps!

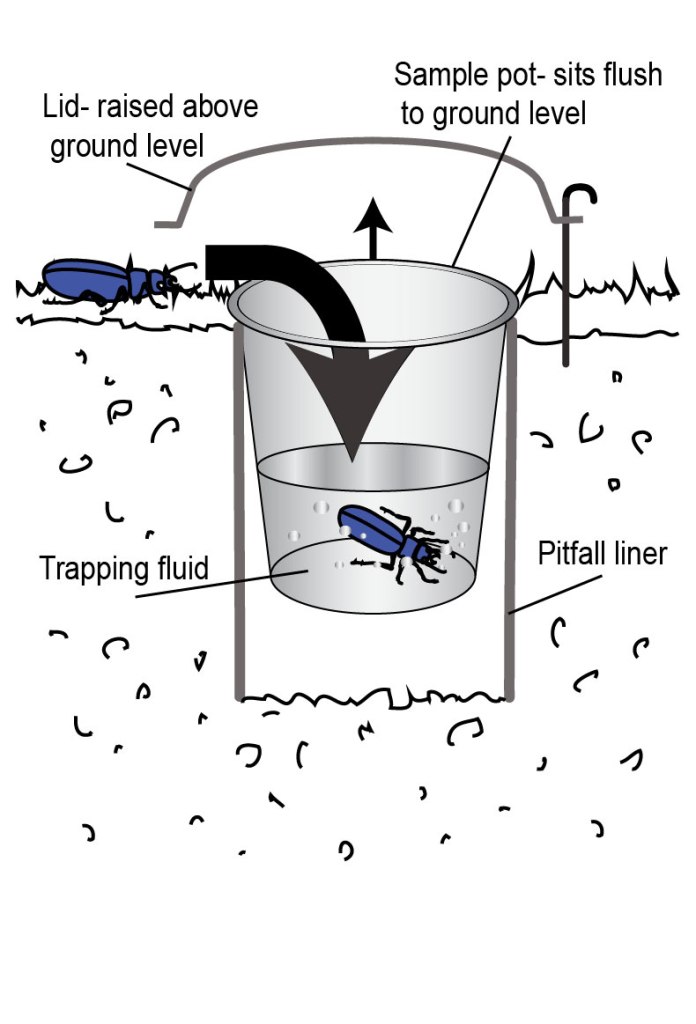

You can check out my other blog posts for details, and what carabids are and why they’re awesome https://beetlekell.wordpress.com/2018/08/19/subterranean-vs-standard-pitfalls-run-1/ but to quickly summarise- carabid trapping is dominated by what I will now refer to as ‘standard’ pitfalls. The beetle wanders along, as they do, and falls into a pot that some entomologist has fiendishly set level with the soil surface. Beetles will all survive the fall, but carabids will get pretty hungry in there, and are not at all sentimental about eating their brethren, so kindly the entomologist will grant them all a quick death with an alcohol solution or similar.

The point of this is to measure ‘activity density’ which is how many and what species are actively walking in a given area at a given time. Scientists use this measure as a proxy for what carabids are actually in the area, carrying out predation for instance, or being affected by pollution perhaps. Problem is that it doesn’t actually measure all the carabids there- some might not walk across the surface often- many fly, many dig, or don’t like being out in the open. There are other measures- such as suction trapping, hand searching, soil coring, and emergence traps. But all of these are really time consuming compared to pitfalls, and some require special or expensive kit. Standard pitfalls are cheap, easy, and also can be compared easily between different sites and studies.

My particular problem with standard pitfalls is that I wanted to find out more about carabid larvae. This is important because when they are growing, they are actually more voracious predators than adults, as they need protein- and so this is vital to add to estimates of predation on crop pests. Additionally, a large proportion of a carabid’s life is spent in their subadult larval form. The larvae live in the soil, and whilst some species do come to the surface to feed (Harpalus rufipes larvae gather weed seeds and hoard them in burrows) most activity is underground. So I can’t really find out much about them with the standard pitfall approach.

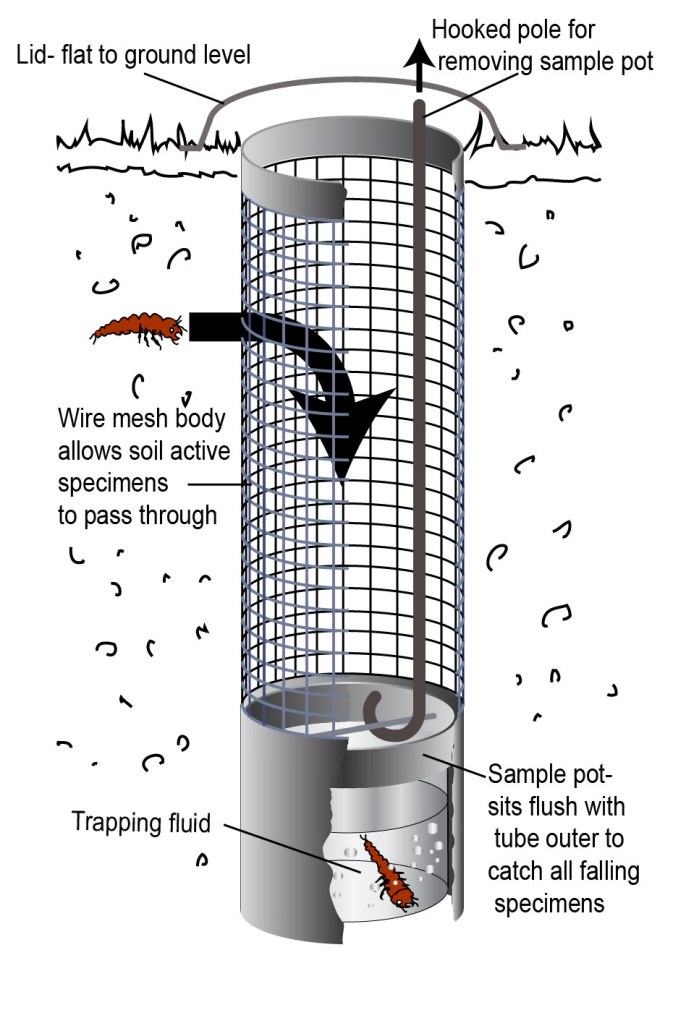

I searched the literature, and tried out soil coring- a day’s (hard) effort returned one Harpalus rufipes larvae. I looked into ways to sift invertebrates out of the soil automatically, and it took some kit that I didn’t currently have. But before I went further, a very knowledgeable entomological colleague told me about subterranean pitfall traps. These are like standard pitfalls, but dug much further into the ground. A wire mesh covers the soil area between the surface and the catching pot, which invertebrates can pass though, and fall into the pot. You empty the traps with a pole and hook- like ducks at the fair!

This was perfect- I tried it out, and it caught carabid larvae with much less effort, and in better condition for identification. The benefit of this versus a soil core is also that it returns the same timeframe as a standard pitfall, rather than a snapshot of what happened to be in the soil at the time that you dug a great hunk of it out. The one obvious disadvantage is a long setting in time, as the soil needs to settle (see previous for more detail).

And so (with much kind assistance) I made 60 subterranean pitfall traps, and put them in a careful experimental design, on an existing crop rotation experiment. I also included standard pitfalls as a comparison. There were replications of traps in different crops, different tillage and different areas relative to the edge of the field. This way I could pick apart the factors influencing what beetles were caught in what traps and where.

Overall, after 2 runs of the experiment I came down firmly in favour of subterranean traps. The hook-a-duck emptying and resetting is quite fun, but mostly I found the samples were less subject to spoiling (by mice etc.) or desiccation (was the year of the drought 2018), and as such much nicer to handle and analyse.

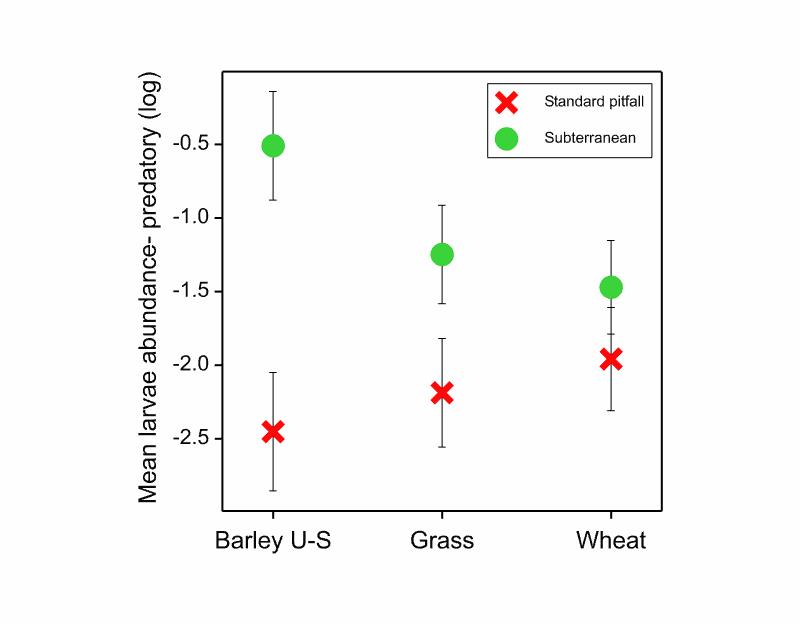

In statistic analysis of the data I found which crop and which trap type were associated with the abundance of carabids, and which species were found where (community composition). It was only when I went right down to species level that I saw influence of tillage on a couple of species. The main story was that for my larvae, subterranean traps revealed a completely different picture of what was active in the crop area. If you look at the red crosses representing standard pitfalls, you might think that there were much less carabid larvae in barley under-sown with grass, but in fact this was just less surface-active larvae! The subterranean traps, the green circles in the diagram, showed that there were in fact the most larvae in this crop, maybe as an attribute of the enhanced soil biota and/or resources. If you want the full story check out my second published scientific paper here [ https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/afe.12397 ]

But that one field could only tell me so much about the larvae. What I’m really interested in is how the larvae occur relative to landscape and management factors- particularly such interventions as field margins. So I deployed my traps again in 2019, across the ~330 ha farm at Rothamsted. Luckily another particularly innovative and dedicated entomological colleague had initiated experimental margins across the farm, in juxtaposition with different crops and landscape features- to investigate if they influenced distributions of moths. With a staggering amount of kind help, I ran 1134 traps in 10 margins, over 4 back-to back runs. See earlier posts regarding my complete exhaustion!

Unfortunate circumstances this year precluding time in the lab have hampered my analysis of the samples, but I have been lucky enough to secure the help of two talented entomologists in getting through the cornucopia of samples I collected. Already we are finding fascinating things, particularly a lot more larvae of various species.

So watch this space for the outcomes… Hopefully I will find time to update you on this before next Christmas!

![57253315_10156745596272631_847769846367125504_n[1]](https://beetlekell.files.wordpress.com/2019/04/57253315_10156745596272631_847769846367125504_n1.jpg)